It was a cold autumn night, sometime in the early 1990s. I stood alone in a quiet field miles from the nearest town, my camera in hand, my breath hanging in the air like smoke. Above me, the sky stretched endlessly, a dark velvet cloth scattered with glittering stars. I knew how to take photographs — I'd spent years mastering light, shadow, timing. But looking up that night, something shifted. The stars weren't just beautiful; they were calling to me. I didn’t just want to see them. I wanted to capture them.

There was just one small problem: back then, if you wanted to learn how to photograph the night sky, you were pretty much on your own. No YouTube tutorials, no friendly blogs, no quick searches for "how to shoot the Milky Way." Astrophotography was a hidden art, a mystery tucked away in scientific journals or whispered about in niche camera clubs.

But I was determined.

Armed with my trusted manual film camera, a sturdy tripod, and a cable release, I took my first steps into the unknown. I guessed at exposure times, cranked open the aperture, and hoped for the best. There was no live view, no histogram, no digital preview. You fired the shutter, crossed your fingers, and waited days for the film to be developed — only to discover mostly black frames, or trails where stars should have been points.

Still, every failure was a lesson. Every faint smudge of light taught me something new about focus, about exposure, about patience. Slowly, painstakingly, I started to piece it together. I learned how crucial it was to pick the right nights, when the moon stayed hidden and the sky stayed clear. I learned to trust my instincts in the dark, to fine-tune focus by feel and memory.

When digital cameras finally emerged, it was a revolution. For the first time, I could see the results instantly. I could correct mistakes on the spot. It transformed not just the images I captured, but the experience itself. No longer confined by the limits of film, I could finally chase the stars with real freedom.

And chase them I did — across the world.

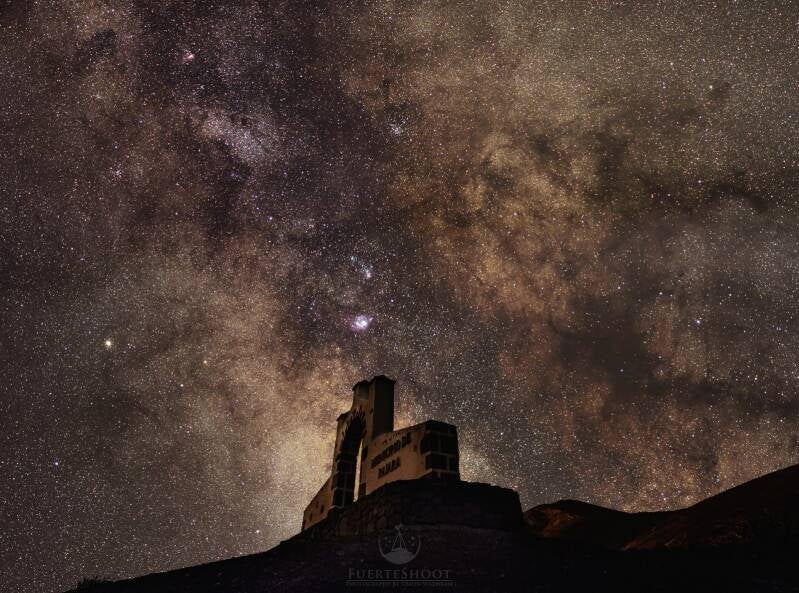

Astrophotography took me far beyond that quiet English field where it all began. I found myself standing under unfamiliar southern skies in Australia, where the Milky Way arched overhead so bright and bold it felt almost close enough to touch. There, in the Outback, with red dust clinging to my boots and the horizon stretching flat and empty in every direction, I captured the galactic core in ways I had once only dreamed of.

At the opposite end of the Earth, I traveled to Iceland, a land of fire and ice, where the Milky Way hangs differently, weaving its way between icy peaks and steaming hot springs. Some nights the sky danced with aurora, adding ghostly greens and pinks to the canvas. Photographing under the northern lights was a challenge and a thrill — the conditions harsh, the cold biting, but the rewards beyond anything words could describe.

From remote deserts to frozen tundras, from the dry stillness of Australia to the stormy skies of the Arctic Circle, my camera and I chased the stars wherever they dared to shine brightest. Every trip, every late night, every frozen finger and lost hour of sleep was worth it — for those fleeting moments when the universe revealed itself, and I could capture a tiny piece of its majesty.

Astrophotography has taught me far more than how to work a camera. It has taught me patience, resilience, and humility. It has shown me that no matter how far we travel or how skilled we become, there is always more beauty, more mystery waiting just beyond our reach.

Thirty years ago, if you had asked me if I'd one day be photographing the heart of the Milky Way from both the red sands of Australia and the icy plains of Iceland, I would have laughed at the absurdity. But life, like the stars themselves, has a way of surprising you if you’re willing to look up, dream big, and keep chasing the light.

And still today, when I stand under a clear night sky, setting up my camera in the silence, I feel the same sense of wonder that started it all — a reminder that some journeys never really end.

Clear skies,

Simon Waldram

Add comment

Comments